Animals in the Maya ecosystems and as utilitarian resource

Since ancient time people have used wildlife for food and clothing. Animal bones are used for tools. Parts of some animals could be traded across the land. So in addition to looking at sacred animals, we at FLAAR Reports also look at the utilitarian aspects of animals for the Maya civilization.

The White-nosed coati

The White-nosed coati species' name is Nasua narica. It's a very intelligent carnivore that belongs to the family of Procyonidae. Its spanish name is Coati, Coatimundi or Tejón; and its Mayan name is chi'ik or ch'we (Pech-Canché et al 2009).

You can identified it because they have a long tail which they hold erect, a small body covered with dark brown to red hair; sometimes they present light brown hair. They have a long snout with a black nose. Its front and rear legs are black, with long claws. These claws allow them to dig the soil and the tree bark in search of food.

The white-nosed coati has a long snout and a black nose. Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i. Copyright FLAAR 2012

The White-nosed coati is a species with social behavior. They have been observed in bands of more than 100 individuals, formed by females and young males. The adult male leaves the band and wanders around by himself. You can also see peccary in large social groups.

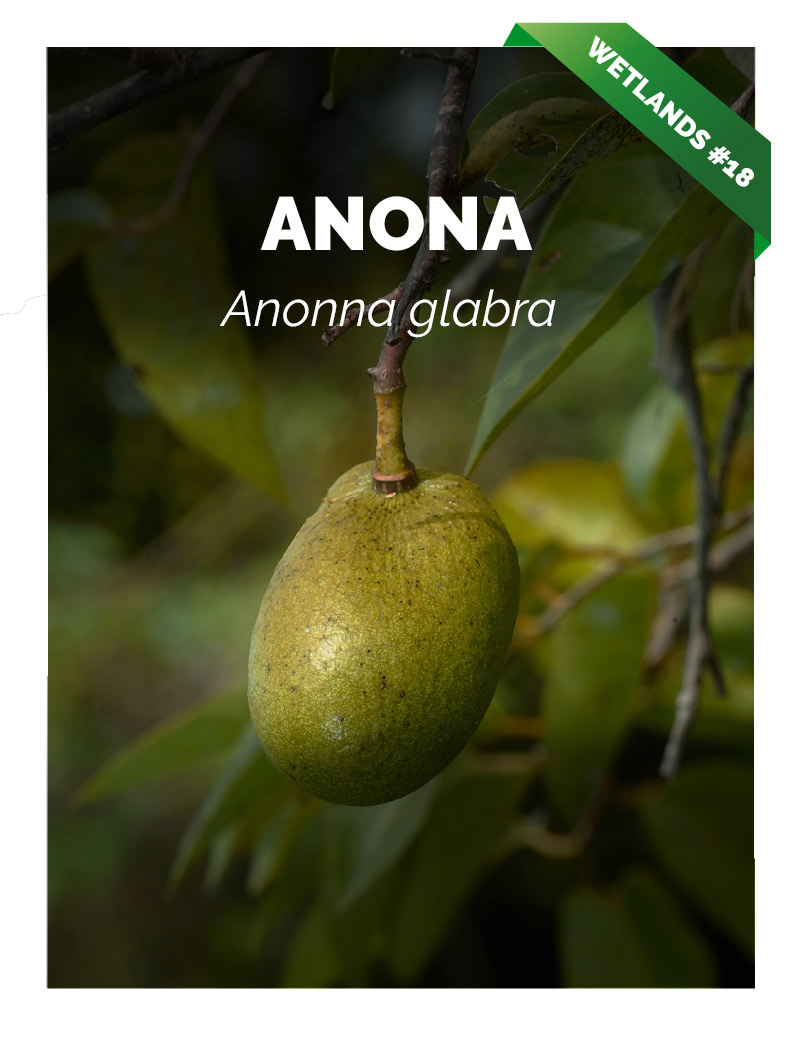

During the day they walk long distances with the band in search for food, which consist mainly on littler arthropods, such as spiders, grasshoppers, coleopters larvae. They have been reported to eat seasonal fruits. They love to eat breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum), sugar-apple (Anona scleroderma), allspice (Pimienta dioica), "zapotillo" (Pouteria dunlandii), sapodilla (Manilkara zapota) and guava (Talisa olivae) among others. They also eat eggs from diverse animals, frogs and little snakes.

According to the National Park of Tikal rangers' there have been some adult males hunting squirrels and wild turkeys.

They are excellent tree climbers since their feet morphology and long tail gives them the grip and balance, so they have been observed resting, hunting and playing in the tree tops. As a tourist visiting Tikal you will see the coatis always on the ground, so it may be a surprise to learn that they sleep in trees.

During the night they tend to rest, though the adult males tend to remain in activity.

The white-nose coatis feet morphology allows it to climb trees easily . Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i at Tikal. Copyright FLAAR 2012

They have their reproductive season from January to February. During that season you can see the males getting together with the band. Since the strongest male gets the chance to keep the females, there are fights among the adult males. They also fight for territory. Sometimes the fights tend to be so intense that one of the males can lose their life during the encounter.

The pregnant females keep the offspring away from the male. They live in nest in the tree cups, and are protected by the band members. However a lot of the offspring do not survive the first years of life, because they are prey of depredators such as hawks, eagles, snakes, felines and other carnivores. Sometimes the offspring gets lost among the bush during long walks.

Where to find coatis?

According to Gompper (1995) its distribution range extends from Central America to the South-western United States. They can be generally found in deciduous and evergreen forests of South Eastern of the United States to Panama and the Northen Part of Colombia. At heights not bigger than 3000 meters over sea level.

Why are they so important?

This is the most abundant carnivore in neotropical forests one of the few that lives in large social groups. Gompper et al 1997 and Valenzuela 1998 seem to focus on the uniqueness of coatis living in social groups, but peccary do also, as do two species of monkeys. Plus many species of bats, though the most carnivorous of the bats, the False Vampire, tends to be more solitary (Hellmuth, personal communication).

Since the coati feeds upon fruits it acts as a disperser of seeds, either ingested or attached to external body parts. It also feeds upon litter arthropods. A study made in Costa Rica by Mora (et al 1999) indicates that the White-nosed Coati acts as a pollinating agent of the Balsa tree (Ochroma pyramidale). Apparently the coati also feeds upon the nectar of the flowers of the Balsa tree. During the visitation there was no damage to the floral structures and the pollen uptakes on facial fur (Mora et al 1999). The pollen then is dispersed by the coati.

Used of the White-nosed coati for the Maya

The White-nosed coati has been used for subsistence hunting. Toledo (et al 2008) made a literature revision about the species used by the Yucatec Maya. Every of the communities registered hunted the White-nosed coati for food.

Nasua narica, species used for subsistence hunting. Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i at Tikal. Copyright FLAAR 2012

Where to see White-nosed coati in Guatemala

The primary place where the FLAAR Staff has seen White-nosed coati is in Tikal, Petén. This is only place where you can seen them wandering around among the ruins paths in the National Park of Tikal, Petén.

Tikal National Park

Tikal is one of the places where you can see White-nosed coati wandering around. Here people have found offspring wandering by themselves. When this happens the offspring are translated to the ARCAS Rescue Center. There they are treated and then they are free to go.

Tikal National Park, Mirtha Cano's experience:

During 2011, during the Biology Laboratory construction and the material donation for the building of a temporary shelter for animals in an emergency, it was possible to learn more about the breeding of two coatis, According to Mirtha Cano the white-nosed coatis where found by Mrs. Roxana Ortiz, a tourist guide of the Hotel Tikal Inn. She brought the abandoned young to the Biology Laboratory, so they can help the coatis.

The white-nosed coatis were two females only a couple of weeks old. Apparently the females fell from the nest and the mother could not rescue them.

One of the coatis rescued by Mrs. Roxana Ortiz at the Tikal Inn Hotel. Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i at Tikal. Copyright FLAAR 2012

In the rescue center, they fed the coatis with soy milk or lactose-free milk, three times a day during the first month. This was a recommendation made by the Director of ARCAS Rescue Center, the Veterinary Fernando Martinez.

Mirtha Cano named the coatis "Lupe" and "Canche". She, along with Mrs. Roxi, did long walks through the Tikal forest in order to get the coatis familiarized with the food they could find available. Gradually the coati youngsters started to feed by themselves.

During this period they could watch how the coatis learned to recognize the harmful insects. Some of the millipedes (Miriapod) cause them irritation in their stomach when they were eaten. Also some of the death worms provoked them stomach ache and vomiting. Some insects also have defense mechanisms that were used against depredators, so they also expel an irritant substance.

Coati at Tikal Inn Hotel interacting with Mirtha Cano. Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i at Tikal. Copyright FLAAR 2012

According to Mirtha there was a time when the coatis could identify an "ultimate pit viper" snake (Bothros asper) with their sensitive sense of smell. The coatis made loud cries when they identified it.

The coatis were getting bigger and bigger with time. And while that was happening they were becoming faster to caught toads, snakes and tarantulas, using their claws to kill their prey.

The wild fruits where a delicacy for their palate. The bread nut (ramon) is very abundant during the months of July and August. The tropical forest offers a big fruit diversity all year long, making the place a feast for the coatis, the birds and other mammals.

The main objective was to raise the coatis during the first months of life, show them their natural habitat, and teach them to locate water and food sources. This way they could incorporate to the female band when they are released.

Mirtha Cano feeding fruit to a coati, a preferred food by Nasua narica. Photo by Sofía Monzón with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i at Tikal. Copyright FLAAR 2012

The coatis were released after five months of care, in areas near the old airstrip and Tikal Inn Hotel in order to monitor them easily. Mirtha observed that the coatis preferred the territory inside the Tikal Inn Hotel. Probably because this is an area with diverse kinds of trees, which provides a god source of food. Since the coatis, Lupe and Canche didn't wanted to join the band, Mirtha and the Park Staff walked along the band so Lupe and Canche could feel comfortable with them and join them.

At the beginning it was hard, though with time both coatis felt comfortable with the band and join them. Even though Lupe had a fight with one of the band members, she is now recovering and ready to join the band again.

Although they might not have the chance to walk with them, they are very pleased to know that they help to rescue and raise two coatis successfully.

- 1999

- White-nosed coati Nosau narica (Carnivora: Procyonidae) as a potential pollinator of Ochroma pyramidale (Bombacaceae). Revista Biologia Tropical. 47 (4): 719-721

- 1998

- Natural History of the White-nosed Coati, Nasua narica, In a tropical dry forest of Western Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología 3: 26-44.

- 2005

- Travelers wildlife guide Belize and northern America. Interlink books. Northampton, Massachusetts.

- 1997

- A field guide to the mammals of Central America and southeast Mexico. New York. Oxford university press.

Updated by Nicholas, August 26, 2015

First posted July 19, 2012 by Daniela Da'Costa