Animal and animal products like bones, horns and skin among others; were used by the ancient Maya not only for food and medicine but also for ceremonies and jewelry. For the ancient Maya, turtles represent more than a source of food nutrients. They were also used as a source for raw materials for domestic and building occupation crafts, ceremonies and ritual elements of household and community level ceremonies and symbols of wealth and power.

The river turtles

In Central America there are 25 river turtle species in 14 genera. In Guatemala there are 11 species reported, according to Köhler (2008):

- Chelydra serpentina

- Dermatemys mawii

- Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima

- Rhinoclemmys aerolata

- Trachemys scripta

- Claudius angustatus

- Kinosternon acutum

- Kinosternon scorpioides

- Kinosternon leucostomum

- Staurotypus salvinii

- Staurotypus triporcatus

The fresh water and river turtles are a diverse group with a wide geographical distribution. It’s a group that contributes to the ecosystem, they contribute with cycling of nutrients and biomass energy flows. Besides, they also represent an important biological component in every trophic level during all their life stages. This is because they have different feeding strategies during their growing stages.

Tortuga blanca, Dermatemys mawii at Sayaxche Peten, Guatemala, Photo by Jennifer Lara.

Turtles in Mayan archeology

Fresh water species are frequently depicted in Early Classic, Late Classic and Post Classic Maya art. Dr. Nicholas Hellmuth suggests that in the PreClassic there could be also some representations as well. The turtles are one of the twelve most common creatures depicted in Classic Maya Art. Turtles are also depicted in the sacred art of several other cultures in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, such as the Mixtec and Aztec.

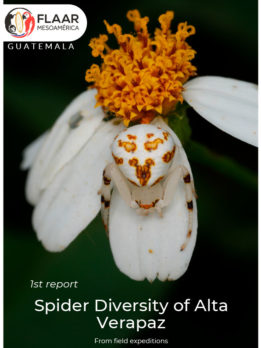

Painted Wood Turtle, Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima, considered to be one of the most beautifully patterned of all turtles. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth at Monterrico, Guatemala, September 2011.

In Copan there is a representation of turtles in a Mayan sculpture. This is one of the largest altars that shows a naturalistic turtle carapace. This is the largest and most naturalistic turtle sculpture of its size (CPN 5, the West Altar of Stela C). But neither of the two heads of this turtle are themselves turtle-like. And the paws are very humanoid. But the carapace is clearly a turtle shell. Over the loincloth apron of the king on Copan Stela C is a relatively naturalistic crocodile upper part of its entire head. The same monument has the turtle altar in front of it.

Guao turtle, Staurotypus triporcatus, in El Estor, Izabal, Guatemala, in this turtles their carapace is distinguished by three distinct ridges, or keels which run its length. Photo by Sofia Monzon, February 2012

Since Quirigua is relatively close to Copan ruins their art and iconography share many features. So it should be no surprise that there is also a turtle altar in the Quirigua area. One of these monuments is the Monument 16. Hewett (1911) which is estimated to weigh 20 tons. The Quirigua Altar N (Renamed as Monument 14), which is almost two meters long by over one meter high, resembles clearly a mythological turtle despite the heavy overlay of additional deities and decorations.

Guao turtle, Staurotypus triporcatus, in El Estor Izabal, Guatemala, they are typically much larger than other species of musk turtle. Photo by Sofia Monzon, February 2012.

Uses nowadays and threats

River turtles are the second group, after the sea turtles, hunted for human consumption and which has proportionately more species in the categories of higher threat than any other group of animals. This overexploitation is the result of their value to the human population. Since they cover a wide range of resources, edible products, like meat, eggs and oil; also medical remedies and pets (species like Trachemys scripta and Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima) they are extremely profitable for commercialist. According to Moll and Moll (2004) when turtles are being excessively exploited, other threats arise from this sector, enhancing their possible extinction. One of the principal factors that contribute to the population decline is the human consumption of turtles as a food resource.

Nowadays most of the turtles that are being captured are not used as food. Instead they are being sold to pet markets, pharmaceutical uses and even collectors, which are increasing the turtle demand.

Mesoamerican slider turtle, Trachemys scripta. Slider hatchlings have a green shell (carapace) and skin with yellow green and dark green striped markings. Markings and colors fade in adults to a muted olive green color. Photo by Sofia Monzon, El Estor, Izabal, Guatemala. February 2012

Where to study turtles in Guatemala

In Guatemala there are some places where they keep turtles in captivity. Such places are CECON (Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas, Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala) in Monterrico, Auto Safari Chapin in Monterrico also and Colecciones de Referencia (Universidad del Valle de Guatemala) among other places.

Mesoamerican slider turtle, Trachemys scripta. The underside of the shell is yellow with dark markings in the center of each scute. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth, Monterrico, Guatemala. September 2011.

Out in the wild most turtles slip into the water the minute they see or hear a boat approaching. So there is not much chance to get a close-up photograph. We at FLAAR contact the local people who have fishing experience, and they indicate us where we can find them.

We always tend to explain to the local people about the importance of conservation, and the important role different animals play in the ecosystem and the human economy.

Scorpion Mud Turtle, Kinosternon scorpiodes at Sayaxche, Peten Guatemala. The characteristic of this species is that its carapace is completely closed, protecting them from predators. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

When we want to photograph turtles we tend to go to CECON in Monterrico, also zoos; Auto Safari Chapin and Nature Reserves (are other places where you can find turtles).

- 1999

- Amphibians and Reptiles of Northern Guatelama, the Yucatan and Belize. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. 380 Pages.

- 2009

- Valoración y uso de Tortugas dulceacuícolas en la Cuenca Baja de Papaloapan, Veracruz. Tesis para optar por el grado de Maestro en Ciencias. Manejo de Fauna Silvestre. Instituto de Ecología, A.C. México 117 pages.

- 2004

- The ecology, exploitation and conservation of river turtles. Oxford Press New York. USA. 393 pages.

- 1995

- A guide of the birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. New York: Oxford University Press 851 pages

- 2004

- Amphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica and the Caribbean Slope.: A Comprehensive Guide. University of California Press. 367 pages.

- 1996

- The Amphibians and Reptiles of the Yucatan Peninsula. Comstock Publishing Associates.

- 2000

- A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of the Maya World: The Lowlands of Mexico, Northern Guatemala, and Belize. Cornell University Press, 416 pages.

- 2002

- The biology of sea turtles, Volume II, CRC Press. 472 pages.It appears that "Vol. II" is not half of a monograph but an update of the initial one (which thereby became "Vol. I"). In other words, you probably only need Volume II. So far their chapter on turtles in Maya art is one of the best that I have found so far.

- 2004

- Las Tortugas acuaticas. Editorial de Vecchi. 127 pages. Several of the photos in this Italian book are better than those in zoology monographs on reptiles of Mesoamerica. Unfortunately, since Millefanti tries to cover water turtles of the entire world, he does not list every single species of each genus. So Staurotypus triporcatus is not included, Musk turtle.

- 1995

- Sea turtles: The Watcher's Guide. Larsen's Outdoor Publishing 128 pages

- 2007

- Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles JHU Press 356 pages

- 2000

- A guide to the Reptiles of Belize. Academic Press 356 pages

- 1988

- Middle American Herpetology: a bibliographic checklist 131 pages

Most recently updated Jun.28, 2012

by Daniela Da'Costa.

First posted Feb. 23, 2012