Written by Sergio D’angelo Jerez on July 16, 2024

Most of the ideas discussed in this article regarding the different meanings that snakes hold in the Maya art where taken from Saturno et al. (2005) Los murales de San Bartolo, El Petén, Guatemala, parte 1: El mural del norte.

Snakes are definitely present and relevant in the cosmovision of many different cultures. For instance, in western culture snakes are linked with the devil, as well as with deception and temptation, attributes that derived from Christianity. The Mayan culture was no exception and had its own way of depicting and understanding snakes. They used them frequently as symbols that held different meanings. Due to the fact that today, 16 of July, is World Snake Day, we want to share how Mayas represented snakes in their art.

Boa imperator at Tikal, locally known as mazacuata. Photo shared by Rony Rodriguez. December 2019.

Snakes are found in many different artifacts, sculptures and ruins from Pre Columbian cultures. They are portrayed in Stela 4 of Takalik Abaj; Structure 5d-33-2º from Tikal; vessels from different cities including Naranjo and Kaminal Juyú; sculptures in staircases from Teotihuacán, Xochicalco, and Chichén Itzá, and many more (Saturno et al. 2005). They were even captured through architecture, such as with the optical effect of the descending serpent in the pyramid of Kukulán, in Chichén Itzá, which happens on every spring equinox.

Regarding their cultural relevance it is evident that the Mayas thought of snakes as symbolic animals since one of the most powerful dynasties is now known as the Kaanul or Snake Head Dynasty (or just Snake Dynasty). This dynasty is thought to be among the only ones that got to build the closest thing to an empire (Taub 2024). Their kings and elite were depicted with an emblem that shows up across the Mayan region called the grinning snake (Vance 2016).

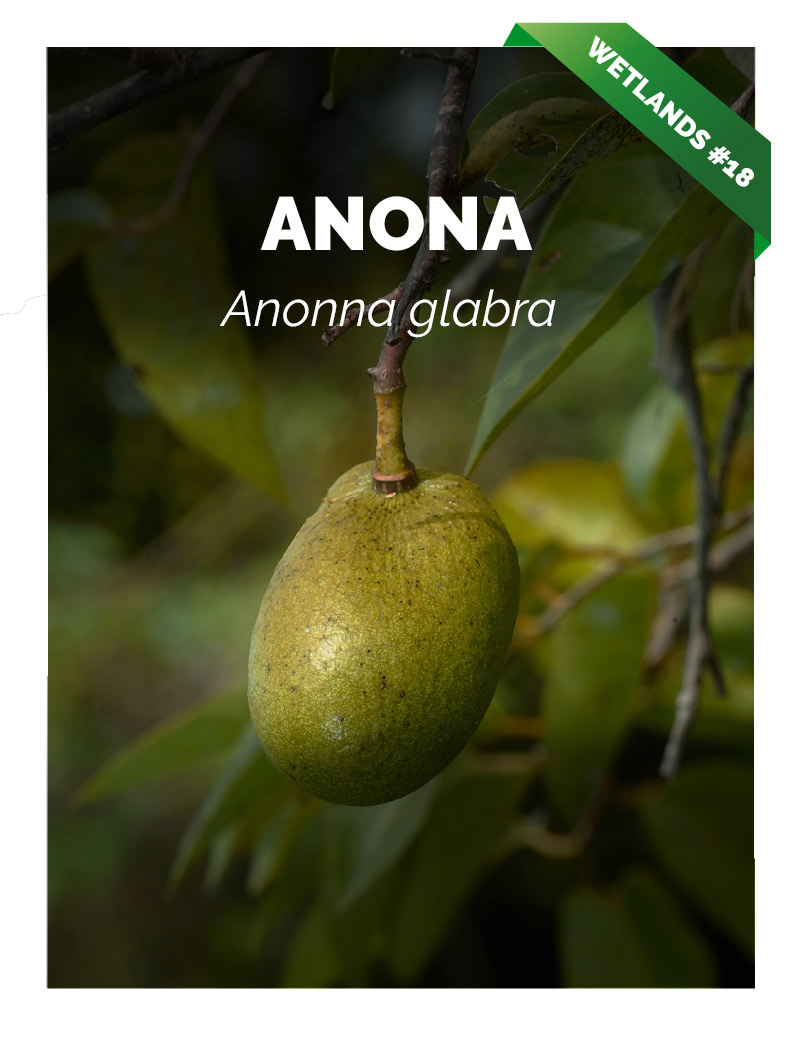

Detail of the triangular pattern on the skin of Bothrops asper, also known in Guatemala as barba amarilla. Photo by Maria Alejandra Gutierrez; Biotopo Chocón Machacas, 2021.

Turning back to snake actual representations, some of the most detailed snakes in Maya art can be found in the Murals of San Bartolo. There are at least 4 of these animals in these murals and two of them are very close in appearance to real species that inhabit the Maya jungle. According to Rodríguez (personal communication, July 10, 2024) one of this species could be Bothrops asper due to the triangular pattern that adorns one of the drawings. Other local species, such as Crotalus spp. and Boa constrictor also have a triangular pattern however.

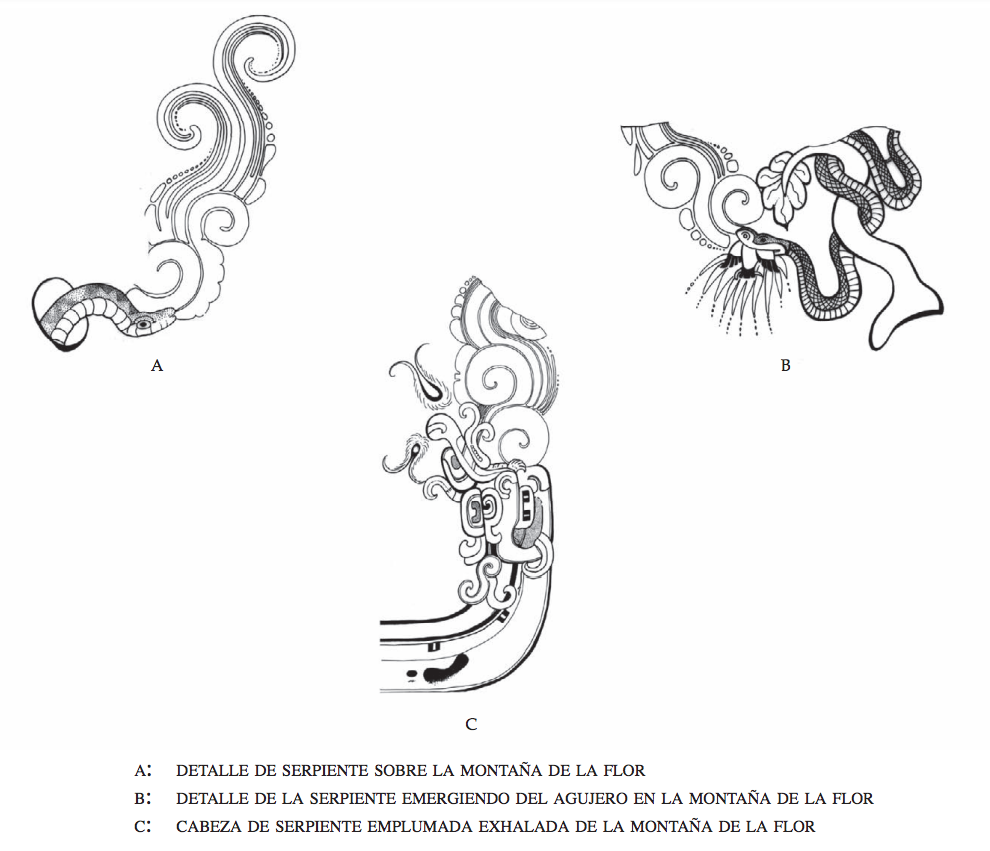

Drawing by Heather Hurst of the snakes depicted in the Murals of San Bartolo. Image retrieved from Saturno et al. 2005, pp. 11.

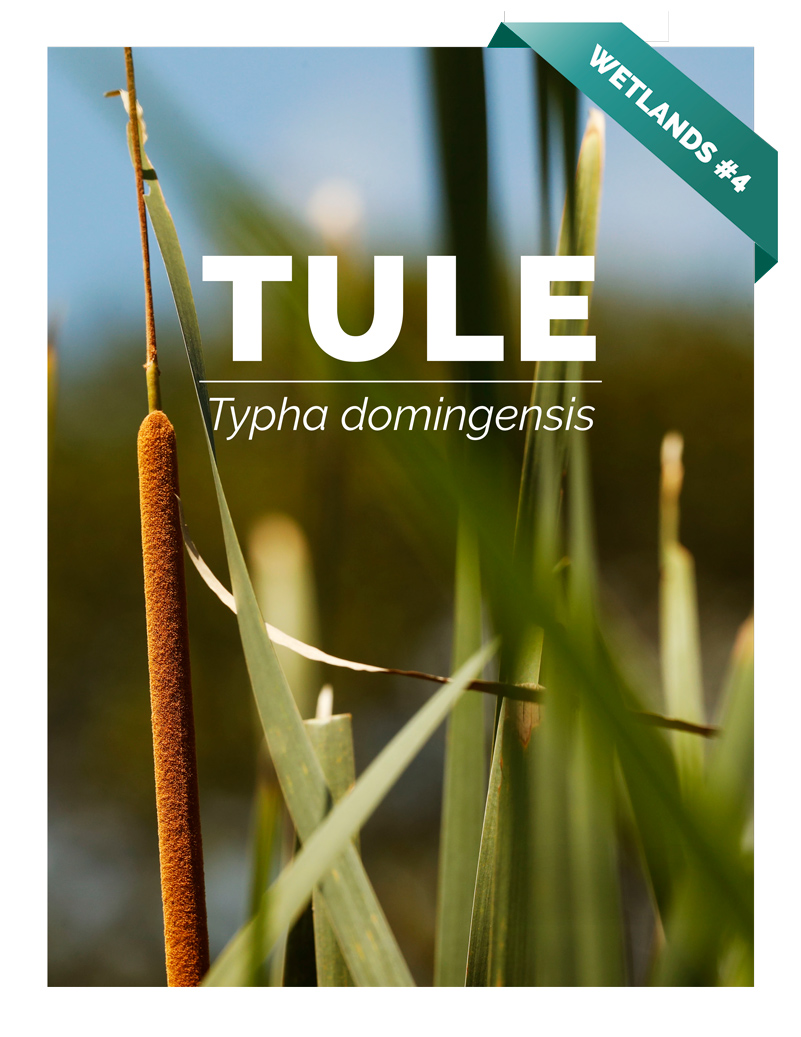

Tree snakes are also depicted in Murals of San Bartolo. They recall species such as Oxybelis fulgidus or Leptophis ahaetulla. One of the illustrations in fact could be Oxybelis fulgidus since it depicts a tree snake eating a bird (Saturno et al. 2005). This species, also known as vine snake or bejuquillo in Guatemala, is very adept at catching birds (Grant 2000).

Oxybelis fulgidus eating a lizard in Santa Elena. Photo shared by Rony Rodriguez. July 2023

When it comes to the meaning that snake figures and pictures had for the Mayas, Saturno et al. (2005) discuss many of their symbology by analyzing the Murals of San Bartolo.

Additional tree snakes from Guatemala. Photo at the left: juvenile of Spilotes pullatus at the Three Fern Savanna, Yaxhá; photo by David Arrivillaga; June 4, 2019. Photo in the middle: Leptophis ahaetulla at El Mirador; photo shared by Rony Rodriguez. Photo at the right: Oxybelis aeneus at Aldea San Juan, Livingston; photo by Víctor Mendoza, 2021.

To begin with, Taube (2001) mentions that snakes were portrayed to symbolize wind and breath. In this regard, they are sometimes outlined emerging from conch shells, perhaps representing how conch shells were used as trumpets (Saturno et al. 2005). In such a case, the snake would denote the air exhaled from these trumpets.

As it happens with water that filters rapidly through the earth, or how air can dissipate so quickly, snakes may have been associated with air because of their undulatory movement and the way in which they can as well vanish quickly in their habitat.

Snakes in addition to jaguars were also reproduced in figures where they stand in front of caves or on mountains. As it is also believed by contemporary tz'utujil people (Christenson 2001), they could stand as guardians or custodies of both caves and mountains (Saturno et al. 2005). On the other hand, when snakes were reproduced emerging from a cave, they could symbolize the wind that blows out of caves, in the form of breath (Saturno et al. 2005).

Crotalus simus rattlesnake at El Mirador. Photo shared by Rony Rodriguez. April 2021.

Moreover, a particular representation of snakes in the Maya world was that of the feathered serpent which was important not only for the Mayas but also for the Aztecs. One of the symbolisms that archaeologists have conferred to the feathered serpent is the incarnation of the east winds, specific to spring and summer (Spence 1923). In that sense and once again, one can see how the Maya associated snakes with wind, yet the feathered serpent was a symbol of nourishing winds that brought life in the spring and summer.

Besides the meanings already discussed in the last paragraph, the feathered serpent could as well represent the East (Saturno et al. 2005) or with a totally different approach, be considered a path in supernatural journeys (Saturno et al. 2005).

Lastly, there is one more meaning conferred to snakes in Maya art. It is considered that snakes emerging out of caves or the earth in general, could not only represent the act of emerging, coming out or leaving (a meaning that is encapsulated in the glyph lok’), but they could also symbolize the myth of emergence which was spread throughout Mesoamérica and the southwest of North America (Saturno et al. 2005). This myth explained how different mythical characters and deities were born from an ancestral cave (Taube 1986).

It turns out to be quite impressive how many different interpretations snakes held in Maya art and how different they are to the ones of modern and western cosmologies. Nowadays, when we are living in what could be a very pragmatic world, it is interesting to learn how much symbolism was given to an animal and how interconnected were the ideas of the Mayas to nature and such influencing forces as the winds.

References

- 2001

- Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community: The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlan. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- 2000

- Oxybelis fulgidus. Animal Diversity Web

https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Oxybelis_fulgidus/

- 2005

- Los murales de San Bartolo, El Petén, Guatemala, parte 1: El mural del norte.

Ancient América, no. 7. Center for American Studies.

www.mesoweb.com/es/publicaciones/caa/AA07-es.pdf

- 1923

- The Gods of Mexico. Frederick A. Stokes Company, New york

- 2024

- Who were the Maya Snake Kings? IFL Science.

www.mesoweb.com/es/publicaciones/caa/AA07-es.pdf

- 1986

- The Teotihuacan Cave of Origin: The Iconography and Architecture of the Emergence in mesoamerica and the American Southwest. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 29/30:39-81.

- 2001

- The Classic maya gods. In Maya: Divine Kings of the Forest, edited by Nikolai Grube, pp. 262-77. Koenemann, Cologne.

- 2016

- In search of the lost empire of the Maya. National Geographic.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/maya-empire-snake-kings-dynasty-mesoamerica