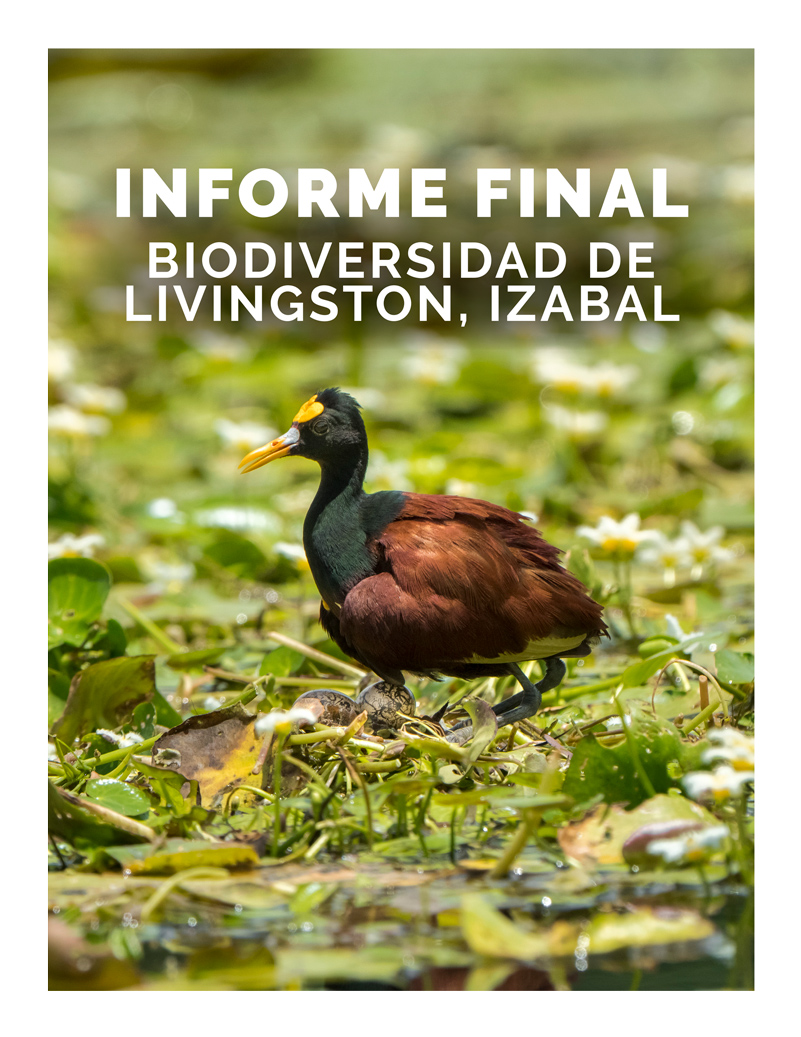

Written by researchers Sergio D’angelo Jerez and Alejandra Valenzuela.

Edited by Sergio D’angelo Jerez.

On September 5, 2024

In commemoration of National Quetzal Day in Guatemala, we encourage you to learn about the national bird of this country, but in a different way. Here you will find an extract from The bird-snake mansion, one of the most beloved literary works in Guatemala, written by Guatemalan author Virgilio Rodríguez Macal. In correlation with different paragraphs of the extract, you will also find scientific data related to real-life elements described by Rodríguez in his tale.

Habitat and distribution

Now, another inhabitant of the rooms of Jorón, the cold,

was Gug, the Resplendent Quetzal…truly, he was the most beautiful of all, the most

beautiful among all those who move

around

the vast extensions of the Green World…

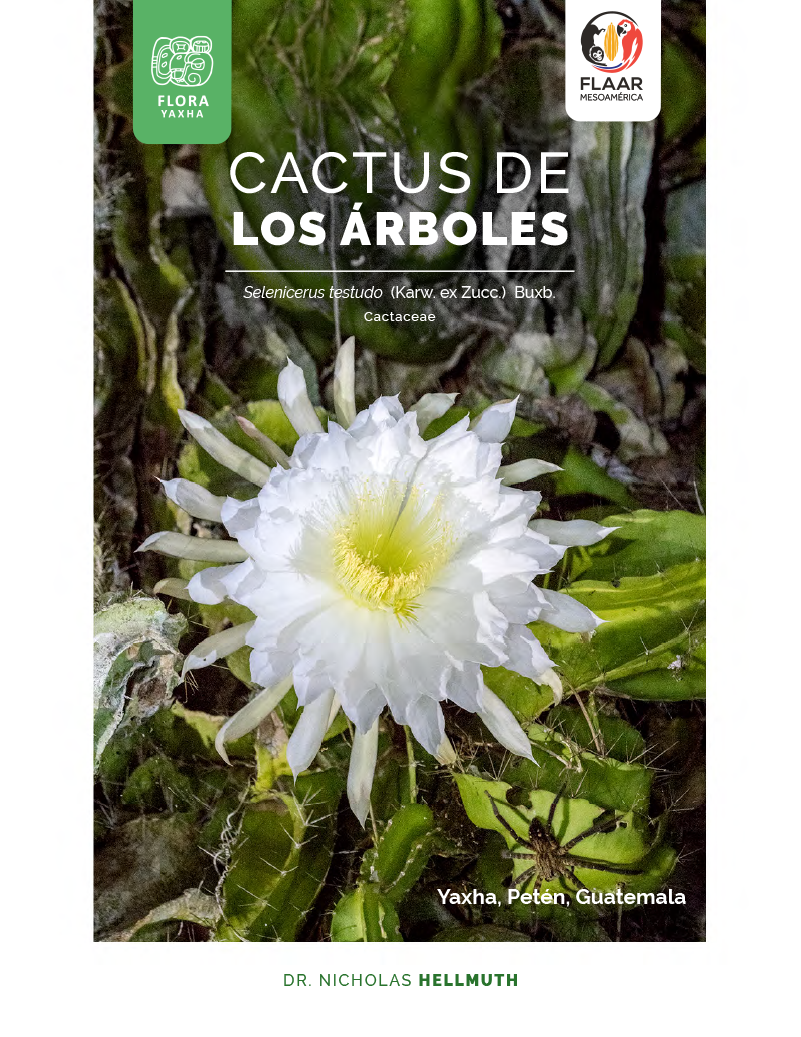

A male Resplendent Quetzal photographed in Ranchitos del Quetzal. Purulhá, Alta Verapaz; June 15, 2017. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

Pharomachrus mocinno, also known as the Resplendent Quetzal, is truly a beautiful bird endemic to Mesoamerica. Its most usual habitats are patches of high-elevation tropical, rainforests and cloud forests in the geographical region that ranges from Chiapas, in Southern México, throughout Central America, and Panama (Renner, 2005). This magnificent bird is usually found at elevations exceeding 1,400 masl, often in very humid forests with abundant broad-leaved oaks (from the Quercus genus), pines (Pinus spp.), and other evergreen tree species (Kappelle, 2006). Studies have found that P. mocinno prefers to inhabit primary forests (forests that have been not disturbed by human activity), and that it is also able to survive and reproduce in some secondary forests (forests that develop after having cleared the original primary forest) (Chokkaingam, 2001; Renner, 2005).

Characteristics

He was known by the name Gug, the snake-bird, since he truly looked like a cute little bird who was always followed by two or more snakes of the most beautiful colors… Gug’s chest was red as blood, with a little white. His body had an unidentifiable color, between blue, gold, and green, as if the rainbow itself lived on him forever, broken into a thousand pieces. Divine, most truly, was the bird-snake, since these snakes that followed him were no other than Gug’s tail, a tail with three or even more of the longest feathers, that looked each as a thin rainbow… When Gug moved around the ground, the leaves, and ferns shook behind his body, as the feathers of its tail went through. True divine snakes are what the feathers of its tail looked like, which followed him submissively as if they were snakes of Heaven, with no poison, and with no evil.

A beautiful male Resplendent Quetzal. Photo shared by Haniel López.

Although the Resplendent Quetzal is famous for what its name describes, a sumptuous bird of iridescent emerald colors, this description doesn’t fit all the members of the species. As can be observed in many instances in nature, P. mocinno presents an evident sexual dimorphism in adults, a condition where males and females from the same species have different appearances (Britannica, 2024; Dayer, 2020). Adult males have long and green uppertail covert feathers that grow beyond the tail, as well as small feathers on the head that form a crest, and bright yellow beaks. This, along with the iridescent gold and green feathers that cover most of its body and the bright red feathers of its belly and undertail covert, are the most distinctive features of a male Quetzal.

The female’s appearance is a bit less eye-catching; the feathers on its belly, throat and sides are grayish brown and their beaks are dark gray. Females also have a crest and uppertail coverts, but these are much smaller and less developed than in males. Nevertheless, females have the same beautiful golden-green feathers on body areas like the crown, back, wings and uppertail coverts (although they do not grow beyond the tip of its tail) (Dayer, 2020).

Behavior

Gug, the Resplendent Quetzal, was the most beautiful bird from all who flew through the four corners of the sky, and at the same time, he was the wisest and most tranquil. There was not a single being in the mountains that didn't stop its own trot, or turned their back on their food, regardless how delicious it was, to contemplate him… All beings in the mountain loved and venerated him, since Gug, the Resplendent Quetzal, was not only very beautiful, but he was also very tender, and a foreigner to scandals… He was different from all the other birds, since he never disturbed the silence with screams or fuss. How different was he from the Chacha, who made her neighbors crazy with all the scandal she made of any trifle, or from Urpa, the Oropendola!... Not to mention, how noisy was Chicó, the Magpie-Jay! He was truly intolerable! When Chicó talked, all the mountain cringed to not listen, the mountain cringed in disgust. Gug, instead, flew as silently as possible, to not bother anyone, as if he let himself slip down from one branch to another, as if he was nothing else than a little piece of rainbow that slipped from one branch to another (...)

A male Resplendent Quetzal posing on a tree fern. Photo shared by Haniel López.

The overall demeanor of the Quetzal has been described as cautious, and it has been reported that it can stay still for a very long time in order to remain unseen. It has also been noted that they place themselves on trees in positions where their bright red belly isn’t exposed, since it is one of its most attractive features (Dayer, 2020).

In terms of its diet, P. mocinno is an omnivorous bird, since it occasionally eats animals like insects or small reptiles, but its main source of food are fruits, making it primarily frugivorous (Dayer, 2020). The capture of small animals is most common when these birds are feeding their young. In fact, studies have shown that the diet of the chicks consists primarily of insects and small vertebrates during the first ten days after hatching, which from then on turns increasingly more frugivorous (Valverde et. al, 1996).

Some studies classify the Quetzal as a specialized frugivore because, although they consume fruits from many families like Theaceae, Verbenaceae and Solanaceae, a large percentage of the food they rely on are species from the Lauraceae family (Wheelwright, 1983). Research has shown that these birds’ digestive tract is adapted particularly to be able to tolerate eating fruits with large seeds, which are common in Lauraceae drupes (Dayer, 2020). This gives P. mocinno a very important role in seed dispersal, particularly when breeding season is over, since during this period they can fly up to 3 km per day (Valverde et. al, 1996).

In other respects, the song of the Quetzal is very unique. It has been described as “a series of deep, smooth, slurred notes in simple patterns, often strikingly melodious” (Stiles & Skutch, 1989). Their vocalizations are varied, but Skutch described the most common ones in his 1944 field-research descriptions. Two of these are vocalizations only registered in males: a high-pitched whistle with two notes during the morning, and a high-pitched call during the day. Other vocalizations, shared by both male and female Quetzals, include: a three-note identification call, an agitation call that is followed by flicks of the tail, and an ascending whistle that they make when they are high in the tree branches or in their nests (Dayer, 2020; LaBastille, et. al, 1972).

Reproductive behavior

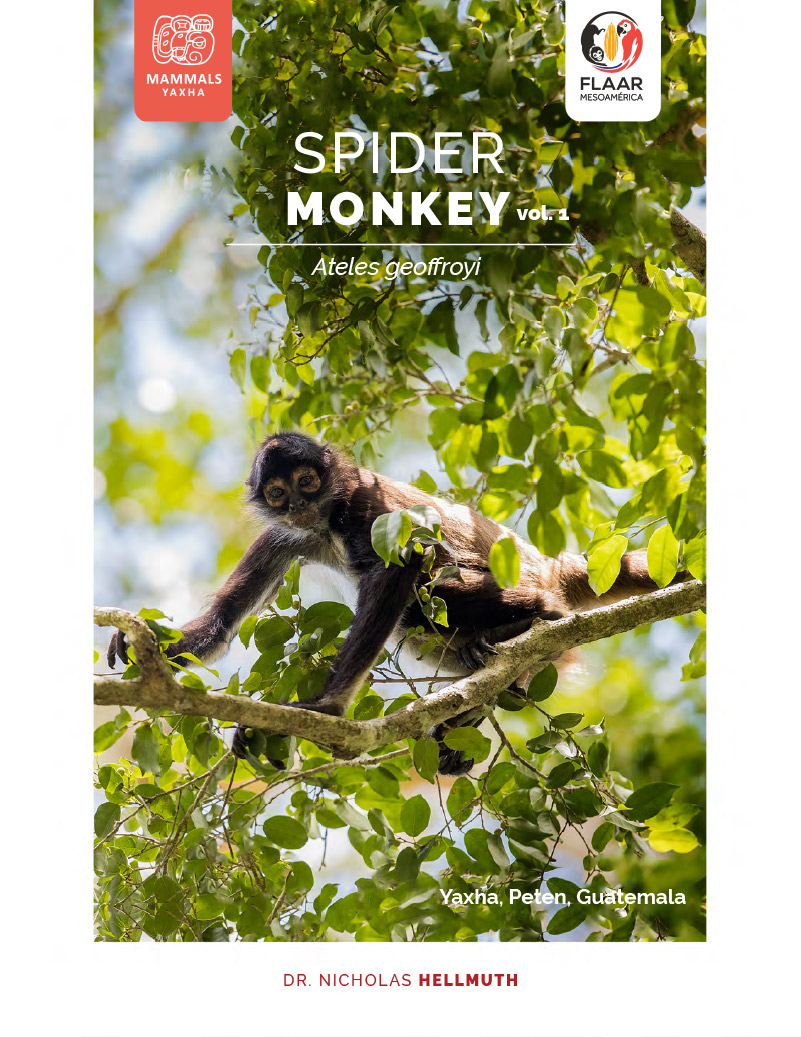

(...) Since Gug was all the opposite, everybody liked, and admired him, as they also did his beauty; Gug only gave a little whistle when he called his females, as he had two or more, and they always followed him, admiring his colors, and his most beautiful tail; Gug’s female is pretty too, but she doesn’t have the majesty of its master. She doesn’t have the snake-tail, nor the tuft that adorns his head, as if it were the crown of a king. Gug’s females followed him everywhere, and it is said that he was a role model, since nobody ever saw Gug mistreat his companion (...)

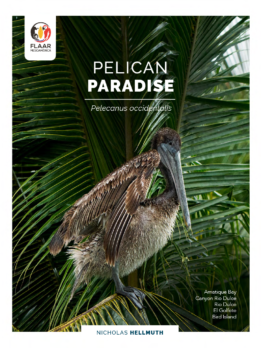

A couple of Resplendent Quetzals visiting its nest at different times. Volcán Tolimán, Sololá. FLAAR Photo Archive by BL.

As is common among bird species, during the mating season, in spring, the male Quetzal displays itself to the female while flying. Males also fly above the treetops while vocalizing, and sometimes chasing the females. After this ritual, the successfully joined pairs return to the breeding areas, which are usually in areas with high elevation. This place chosen by the pair is believed to become the shared nest that they create for their offspring (Dayer, 2020). A correlation has been found between the period in which reproductive behavior starts and the season when fruits are the most abundant, concluding that the breeding season is usually around March and June (Wheelwright, 1983). P. mocinno couples build their nests in cavities that they find, or carve out high up in tall trees (>8m), stumps, or similar locations (Dayer, 2020). Both males and females incubate the eggs until they hatch. Then, both of them look for food, and feed their babies.

Threats, vulnerability and cultural value

(...) Gijs passed, and during one of many, a man, a lonely Achí, had gone to hunt one Gug, the Resplendent Quetzal, smuggling, when he saw a monkey crouched at the foot of a tree (...) (Rodríguez, 2008).

Forests are cleared to make more land for agriculture. Senahú, Alta Verapaz; March 6, 2020. Photo by Senaida Ba.

The Resplendent Quetzal was central in the beliefs and traditions of Pre-Columbian civilizations. For instance, Quetzalcóatl, one of the main gods in both Maya and Aztec cosmovisions, was represented with the head of a serpent adorned with feathers of the Resplendent Quetzal (BirdLife International, 2008).

Moreover, feathers of the Resplendent Quetzal were also used in headdresses which were only worn by rulers. These were gathered from wild birds, but since the Quetzal was held so important, it was prohibited to kill the birds. The penalty of doing so was death (BirdLife International, 2008).

And that’s not all. This bird was considered so important that it is theorized that both the Maya and Aztec civilizations immortalized it in their pyramids. For instance, it is thought that one pyramid at Chichén Itzá was designed in such a way that the echoes of sharp sounds in its interior resemble the bird’s noise (BirdLife International, 2008). In Tikal, Guatemala, local guides would describe the same phenomenon, which happens every time you clap in a certain position outside one of the pyramids.

Nowadays, the Quetzal still holds cultural value. For instance, the unit of monetary currency of Guatemala is called quetzal, and the species is also the national bird.

However, despite its great beauty and cultural significance, this doesn’t seem enough to protect the beautiful Quetzal and its habitat. Its population is continually decreasing and it is menaced by different threats. These include deforestation, fires, and wildlife trade (BirdLife International, 2024). In 2024 only, fires were reported in three main areas inhabited by the Quetzal in Guatemala. These were the Agua Volcano, the area surrounding the Quetzal Biotope Natural Preserve, and Sierra de las Minas. A previous fire in 2021 in the Atitlán Volcano, Sololá, also consumed part of one of its natural habitats.

At this point, the tale is over, and Rodriguez continues describing other events, and inhabitants of the snake-bird mansion. That’s how this article also comes to an end. However, there'll hopefully be another chance to visit its mansion and learn of other of its inhabitants.

A final invitation for this article would be to take care of the snake-bird environment, and to continue learning not only about this bird, but also about the green world we share with it to commemorate the Quetzal National day.

References

All the text put in cursive is an extract from The snake-bird mansion (2008) by Virgilio Rodríguez Macal.

- 2008

- The Resplendent Quetzal in Aztec and Mayan culture.

Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/the-resplendent-quetzal-in-aztec-and-mayan-culture.

- 2024

- Species factsheet: Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno.

Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/resplendent-quetzal-pharomachrus-mocinno.

- 2024

- Sexual dimorphism. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Available online: www.britannica.com/science/sexual-dimorphism.

- 2020

- Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno), version 1.0. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- 2006

- Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical Montane Oak Forests Volume 185. DOI:10.1007/3-540-28909-7

- 1972

- Behavior and Feather Structure of the Quetzal. The Auk, 89(2), 339–348. DOI:10.2307/4084210

- 2005

- The Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) in the Sierra Yalijux, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. , 146(1), 79–84. doi:10.1007/s10336-004-0060-7

- 2008

- La mansión del pájaro serpiente. Guatemala. Editorial Piedra Santa.

- 1996

- The Diet of Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus Moncinno mocinno: Trogonidae) in a Mexican Cloud Forest. Biotropica, 28(4), 720. DOI:10.2307/2389058 10.2307/2389058

- 1983

- Fruits and the Ecology of Resplendent Quetzals, The Auk, Volume 100, Issue 2, Pages 286–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/100.2.286